Dr. Utkarsh Sinha

Dr. Utkarsh Sinha

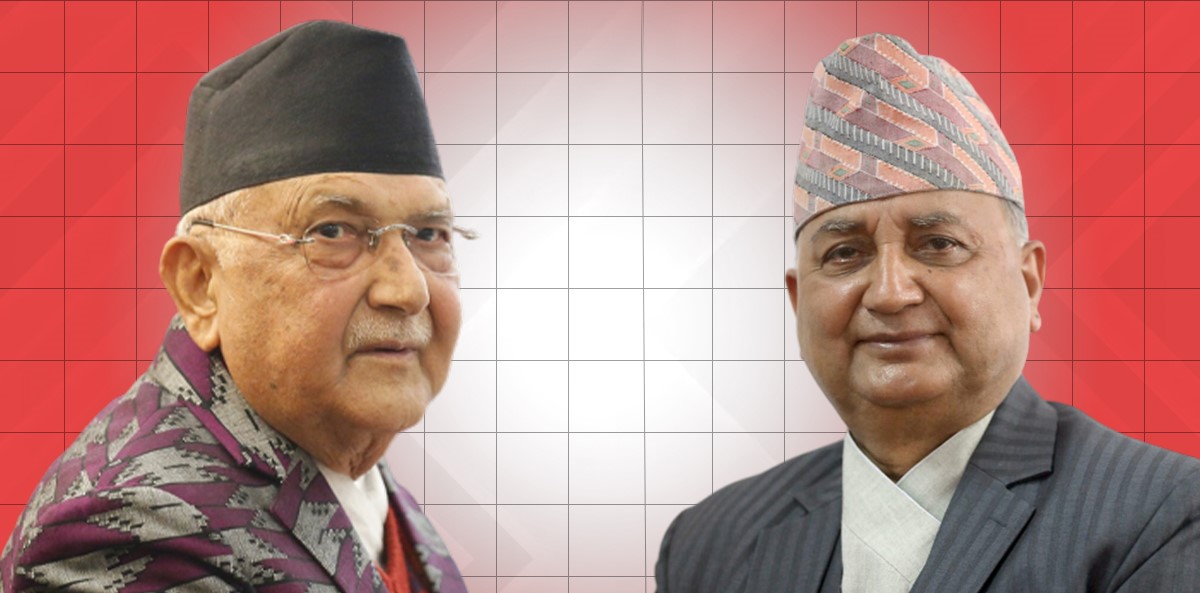

The recent internal elections of Nepal’s Communist Party (UML), in which KP Sharma Oli’s camp registered a sweeping victory and the Ishwar Pokhrel group suffered a heavy defeat, will not be confined to mere organisational arithmetic. Instead, the outcome is set to reshape Nepal’s overall power equations, the trajectory of left politics, the structure of the opposition, and even external relations with countries like India and China in the coming years. This victory has come at a time when Oli has already served multiple terms as prime minister and his party has repeatedly emerged as a decisive force in Nepal’s “musical chairs” style of politics. As a result, the reassertion of his dominance within UML will have a deep impact on national politics as well.

Power balance within UML

In UML’s 11th General Convention, more than 2,200 delegates voted to elect a new leadership, in which Oli, as party chair, secured a huge lead over Ishwar Pokhrel. This clearly indicates that the organisational majority still trusts Oli’s leadership style, his aggressive persona, and his ability to win elections, even though youth movements and his controversial tenure in power have raised serious questions about his popularity. The Pokhrel camp had hoped that disgruntled leaders, former president Bidya Devi Bhandari, and his grip in certain provinces would help mount a strong challenge. However, the results revealed that an “anti-Oli consensus” has not yet crystallised at the party cadre level.

Despite Ishwar Pokhrel’s defeat, the victory of some of his allies to the central committee and other posts shows that a “weak but surviving” alternative current will continue to exist within UML. In the future, this current may either push for reforms from within Oli’s leadership, or, in the event of a major political jolt, re-emerge as a separate pole.

Leadership style: Centralisation vs internal democracy

The Pokhrel faction had openly alleged that the statute amendment and delegate-selection process suited Oli’s design and was being used to institutionally weaken dissenting voices. In this context, the moral legitimacy Oli has derived from this electoral victory may encourage him to push further towards centralisation in the coming years, as he can now argue that party workers themselves back his “strict, discipline-driven line”.

On the other hand, Pokhrel and his supporters can now claim that they kept democratic debate alive within the party as “principled dissent”, since they did not leave UML after the defeat, nor did they opt to form a separate party. This is a form of political capital they can deploy if Oli is engulfed in any major political or moral crisis in future, such as corruption charges, suppression of youth protests or controversial constitutional amendments.

Impact on national power equations

Oli is already known in Nepal’s politics as a “political survivor” who, despite being ousted from power multiple times, has repeatedly engineered new coalitions to return to the prime minister’s chair. Even after the 2022 elections, UML and the Nepali Congress emerged as the two largest parties, and in the months that followed, Oli played a central role in forming and toppling governments—sometimes with the Maoist Centre and sometimes with the Congress. In such a situation, a stronger grip within UML means that Oli will be even more decisive in any future coalition negotiations, because internal voices that could challenge him have now been pushed further to the margins.

The flip side is that opposition parties or potential coalition partners will now find their “soft contact points” inside UML—leaders like Ishwar Pokhrel or his confidants—losing bargaining power. When a single leader commands near-total dominance in a party, external actors understand that the real negotiations and “deals” have to be struck only with him. Ultimately, this makes power-sharing politics more personalised, erodes policy-based consensus, and weakens the tradition of programmatic alliances between parties.

Left politics and communist polarization

Over the past decade, Nepal’s communist politics has oscillated between splits, reunifications and coalition experiments—UML and the Maoist Centre once unified, then split, then partnered in government again, only to fall apart later. Oli’s strong comeback could generate two possible trends within the left spectrum:

- First, UML could emerge as a relatively stable and disciplined left party, consolidating its identity distinct from the Maoists.

- Second, if Oli continues to play coalition politics in an opportunistic manner—allying sometimes with the Maoists and sometimes with the Congress—left politics may further drift away from ideology and remain trapped in sheer power calculus.

Ishwar Pokhrel’s defeat also implies the weakening of that line within UML which envisioned the party moving towards a more institutional, collective leadership with a “guardian role” for the chairperson. Pokhrel had suggested that Oli step back from active day-to-day politics and assume the role of party patron. Instead, it now appears likely that, rather than ideological debates, personalised polarisation—Oli supporters versus anti-Oli factions—will continue to dominate UML’s internal political frame.

Effect on youth, movements and democratic discontent

The most tragic aspect of Oli’s previous tenure was the crackdown on youth movements and decisions like social media bans, which led to the deaths of several protesters and ultimately cost him the prime minister’s post. Against this background, the fact that UML’s rank and file have once again given him an overwhelming mandate sends a signal that the party has not fully internalised the public anger; instead, it treats it as a temporary disruption and chooses to move on. This could intensify unease among youth and civil society, who may feel that mainstream parties still prefer “electoral management” to accountability when it comes to legitimising leadership.

It is, however, possible that Oli may treat this internal victory as a “last chance” to partially repair his image—by pushing an anti-corruption and employment-oriented agenda, improving governance, and taking a somewhat softer line on digital rights to win back youth support. Yet, given his past record, such trust will not be easy to earn, and the opposition—especially the Maoist Centre and other centrist parties—will keep using these issues as political ammunition.

India–China and regional diplomacy

Oli is known as a leader who, on the one hand, deepened Nepal’s engagement with China, and on the other, generated tensions with India through boundary disputes, a new political map and nationalist rhetoric. In later phases, he also displayed pragmatism by attempting to repair ties with the Indian leadership and floated the idea of a “national consensus” government by working with the Nepali Congress, indicating that, in foreign policy, he is more pragmatic than ideological. A stronger position for him within UML means his personal priorities will weigh heavily on Nepal’s future foreign policy—whether in relation to Chinese investment projects, or to India–Nepal trade, water resources and security cooperation.

If the Pokhrel camp—which emphasised internal democracy and carried a slightly different tone—gets weakened further, internal debate on foreign policy may also shrink, and crucial strategic decisions could be confined to a limited circle. Regionally, this will send a clear signal that Nepal is entering another “Oli-centric” phase in which both Beijing and New Delhi must primarily deal with one dominant face, rather than a broad left front or a collective leadership.

Future challenges and possible scenarios

Oli’s biggest challenge now is to manage internal discontent, because despite electoral defeat, Ishwar Pokhrel and his supporters have not disappeared; they remain inside as a form of “organised dissent”. If Oli chooses merely to sideline them, the possibility of a future party split, rebellion or anti-Oli coalition—especially if he returns to power and once again takes controversial decisions—will remain very real.

For Nepal’s broader politics, the result signifies, on one hand, a measure of stability—since a major party now has an undisputed leader at the helm—but, on the other hand, it also raises the risk that the same old personalised, power-centric politics, where coalition-making and breaking is the main game, will dominate again. In this sense, Oli’s big win within UML opens a new chapter in Nepal’s democratic journey, where the possibilities of both stability and instability run parallel. Much will depend on whether he converts this mandate into an opportunity for reform, or uses it merely as an instrument of power projection to continue down the old path.

Jubilee Post News & Views

Jubilee Post News & Views